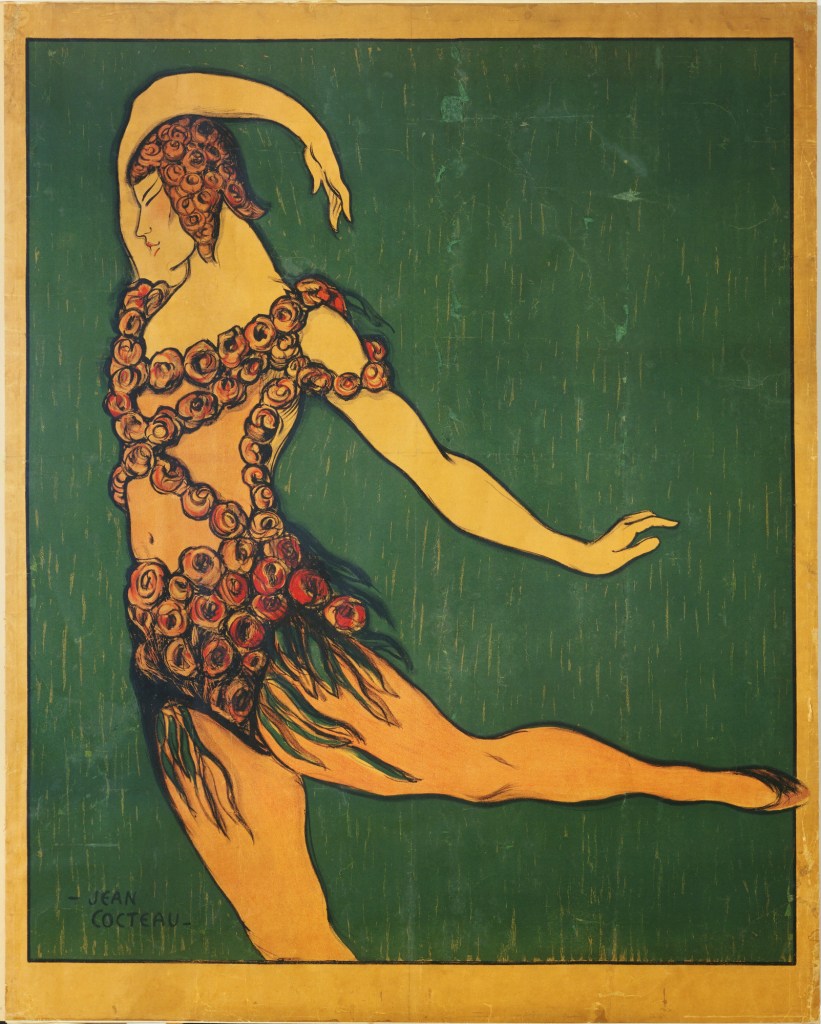

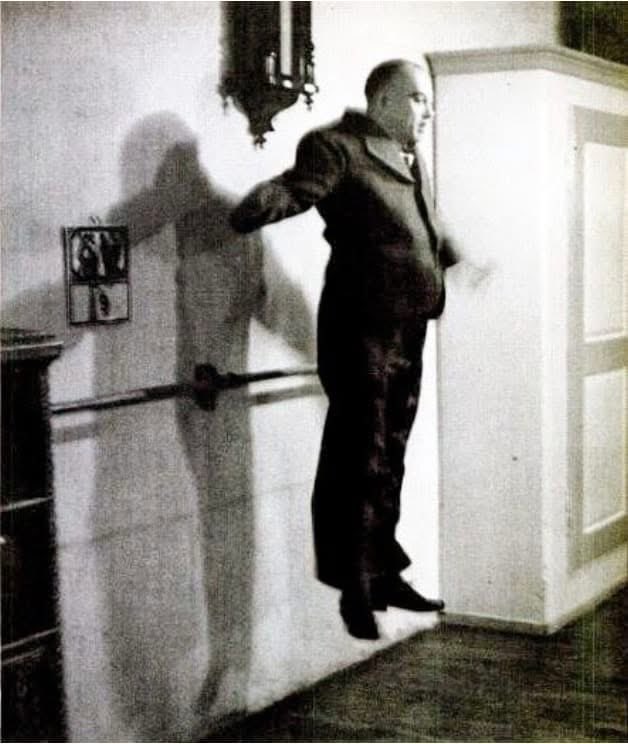

Winter, 1939. Vaslav Nijinsky, after twenty years, rose once more into the air. Twenty years of his body revolting against him, claimed by silence, hospitals, and the tremors of an unraveling mind. His final, fractured leap was to an audience of journalist Jean Manzon and a dancer who just performed The Jester at a mental institution in Switzerland. This has been remembered as his last jump: not the volcanic brilliance of Le Spectre de la Rose or Afternoon of a Faun, but the ghostly echo of a saint attempting to remember a prayer erased long ago by illness. History recorded a last glimpse of grace through Manzon’s camera lens, but the leap did not save Nijinsky. It did not unfasten the rusted halo of his schizophrenia.

Three years earlier, on the 7th of September, 1936, the last known Thylacine died due to neglect and exposure at the Hobart Zoo. Its striped back was left beneath a sky that had already forgotten what it had killed. There was no trumpet announcing its end, no consecration was offered. The extinction was bureaucratic, procedural, banal, a resigned exhale after decades of held breath.

These two moments, Nijinsky’s final leap in 1939 and the thylacine’s last breath in 1936, form a broken constellation in the psychic sky of modern myth. One a human body defying gravity for the final time, the other a species collapsing into silence. Both gestures are soaked in poignancy, and both are misread as a form of closure.

Now, as science reaches its trembling hands towards the resurrection of the thylacine, we find ourselves choreographing another illusion: that its de-extinction will absolve our original acts of violence, that a new striped body pacing behind glass will rearrange the moral architecture of history itself.

Nijinsky teaches us otherwise.

His final jump did not erase the fragmentation of his mind or heal the rot of the century that consumed him. He returned to his silence, to the earthly body that once touched divinity but then struggled to remember his own name. The wounds endured, both his and ours, and so too will the thylacine’s as it moves through its second life like a punctuation mark at the end of a sentence already soaked in blood. Man will point and say: Look, we’ve healed the past! But, the structures that engineered the extinction of the thylacine and countless other creatures will remain intact beneath the surface of the miracle. We will watch with the same hunger and arrogance, the same casual disdain for breath and bone.

The schizophrenia of mankind is not cured by spectacle. It is merely decorated by it.

We are a species that exterminates and then romanticizes, that murders then resurrects. We perform mercy only as theatre. The reborn thylacine will not be freedom, but a symbol walking through the afterlife of our guilt, a living footnote beneath a history we leave unacknowledged.

Like Nijinsky’s final jump, the thylacine’s resurrection will glow for a devastating and beautiful moment before receding back into the same world that made its death inevitable the first time. These are two elegies mistaken for redemption.

History applauds these moments, photographs the miracles, and then continues, uncorrected, forward. Beneath it all, the incurable tremor persists, a civilization pirouetting endlessly between guilt and god-complex, resurrection and repetition, mistaking the brief shimmer of glory for the long work of moral transformation.

This is part of a larger work in progress entitled The First and Last of the Thylacines.

Leave a comment